Heard this carol?

Have you heard/sung the song Twelve Days of Christmas? Even if you have, check out the John Denver and the Muppets version. It is fun!

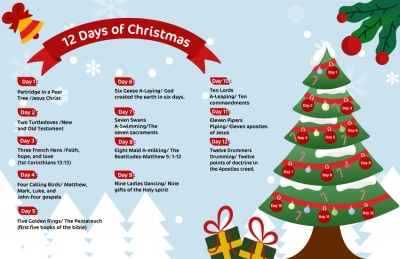

December 25 marks the official start of 12 days of Christmas. And this Christmas carol tells us what those twelve days are about.

In Christian belief, the 12 days of Christmas mark the period between the birth of Christ and the coming of the Magi, the three wise men. It ends on January 6 (Epiphany or Three King’s Day). The four weeks preceding Christmas are described as Advent, which begins four Sundays before Christmas and ends on December 24.

In the carol, the singer brags about all the wonderful gifts the group received from their “true love” during the 12 days of Christmas. Each verse is an addition to the previous one, and the song gets longer and longer. The lyrics to “The 12 Days of Christmas” have changed over the years.

The one below is the most popular version.

On the first day of Christmas,

My true sent to me

A partridge in a pear tree.

The song then adds a gift for each day, building on the verse before it, until you sing of all 12 gifts together.

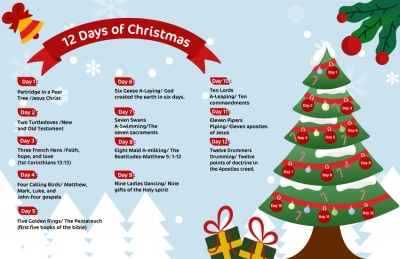

Day 2: two turtle doves, Day 3: three French hens, Day 4: four calling birds, Day 5: five gold rings, Day 6: six geese a-laying, Day 7: seven swans a-swimming, Day 8: eight maids a-milking, Day 9: nine ladies dancing, Day 10: 10 lords a-leaping, Day 11: 11 pipers piping, Day 12: twelve drummers drumming.

The song first appeared in a 1780 children’s book called Mirth With-out Mischief. Some historians think it was first sung in French. Whatever the language, it is a “memory” game, in which singers try to remember the lyrics and lose points if they make a mistake.

An English composer, Frederic Austin is credited with the version most of us are familiar with. In 1909, he set the melody and lyrics. When you sing the stretched “five go-old rings”, you should remember him. It was his idea.

Now let’s see why these gifts were chosen.

Partridge in a pear tree

It is not likely that you will find a partridge in a pear tree. Partridges are ground-nesting birds, and avoid flying high to perch in pear trees. The word “partridge” comes “perdix,” the Greek word for the bird. This in turn comes from a verb meaning “to break wind”, which refers to the sound of the wings as the bird takes off.

Two turtledoves

The turtledove is a bird and the word is used to refer to a beloved one. The “turtle” in the name is based on the Latin turtur that sounds like the bird’s distinctive call.

Turtledoves live in pairs, which show affection for the mate. This bond between birds has been described in Literature. In his poem of 1601 “The Phoenix and the Turtle”, Shakespeare refers to a tale of love between a phoenix and a turtledove.

Three French hens

We don’t know why people will give chicken as a Christmas gift, but poulets de Bresse (Bresse chicken) is a sought-after French hen, so the receiver may accept the three French hens. The word hen comes from the Old English hen(n), and is related to the Latin canere, “to sing,” so it is appropriate to be added to a carol.

Four calling birds

Most of us sing this line as “calling birds,” but in a 1780 version of this song, the line was “colly birds.” Around the time this song was published, “colly” in British dialects meant “dirty, grimy or coal black.” Frederic Austin’s 1909 version of “Twelve Days of Christmas” replaced colly with calling.

Five golden rings

We know what gold means. It stands for the valuable metal, and is form an ancient (Proto-Indo-European) root meaning “to shine.” This same root ultimately gives the word yellow, another meaning for “golden.” In the song, this lyric was originally “gold rings”, rather than “golden rings.”

Six geese a-laying

Birds again! But goose because it stands for a variety of things. It can refer to “the female web-footed swimming bird,” “a foolish person,” or “a poke in the back to startle someone.” There is also the idiom wild-goose chase, which refers to “a wild or absurd search for something unattainable.”

Seven swans a-swimming

It is comforting to know that the seventh day gift of seven swans are swimming and not singing! Swans do not have a voice that will get them to be included in the Christmas choir, so it is good these raucous birds will glide in the water and perhaps keep quiet.

The word swan means “the singing bird,” and is related to the Old English geswin, which means “melody, song” and swinsian, which means “to make melody.”

Eight maids a-milking

Since this song’s appearance in the late 1700s, “milk” in its verb form has stood for a range of actions, mostly shady. In card games, “to milk the pack” means “to shadily deal cards by pulling them from both the top and bottom of the deck.” “To milk at the horse race” was “to throw a horse race.” In the late 1800s, milk meant “to bug a telephone.”

Nine ladies dancing

The word “lady” is from the Old English hlaefdige, thought to literally mean “loaf-kneader” or, more broadly, “wife of a lord.” It entered English in the 1300s. The word dance comes from the Old French dancier. People preferred it to the Old English word for dance, sealtian.

Ten lords a-leaping

The word “lord” comes from the Old English word hlafweard, which literally meant “loaf-keeper.” Remember, “lady” means “loaf-kneader.” The origins of these words tell us about a social structure where wives made the bread and husbands guarded it. Of course today both can be breadwinners.

Eleven pipers piping

The word pipe, as a verb, meaning “to play on a pipe,” can be traced back to the Latin pipare, meaning “to peep, chirp.” It also means “to make a shrill sound like a pipe,” “to lead or bring by playing a pipe,” and, in baking, “to force dough or frosting through a pastry tube.”

Twelve drummers drumming

The word “drum” is the back formation of the longer word drumslade, alteration of the Dutch or Low German word trommelslag, which meant “drum beat.”

Picture Credit : Google