In November 1922, after years of searching, British archaeologist Howard Carter stumbles upon a buried flight of steps while working in Egypt’s valley of the kings and unearths the entrance to the 3,000-years-old tomb of Tutankhamun. In the months that follow, thousands of priceless artefacts are recovered in one of the greatest finds in the history of archaeology.

By the Spring of 1922, British Egyptologist Howard Carter, financed by George Herbert. Earl of Carnarvon, had spent six seasons – November to April each year, avoiding the intense heat of summer- searching for a royal tomb he believed was waiting to be discovered on the west bank of the Nile, in the famed Valley of the Kings. With little to show for his efforts, it was agreed that the quest would be abandoned after one final, short dig of two months only, to start in November of that year.

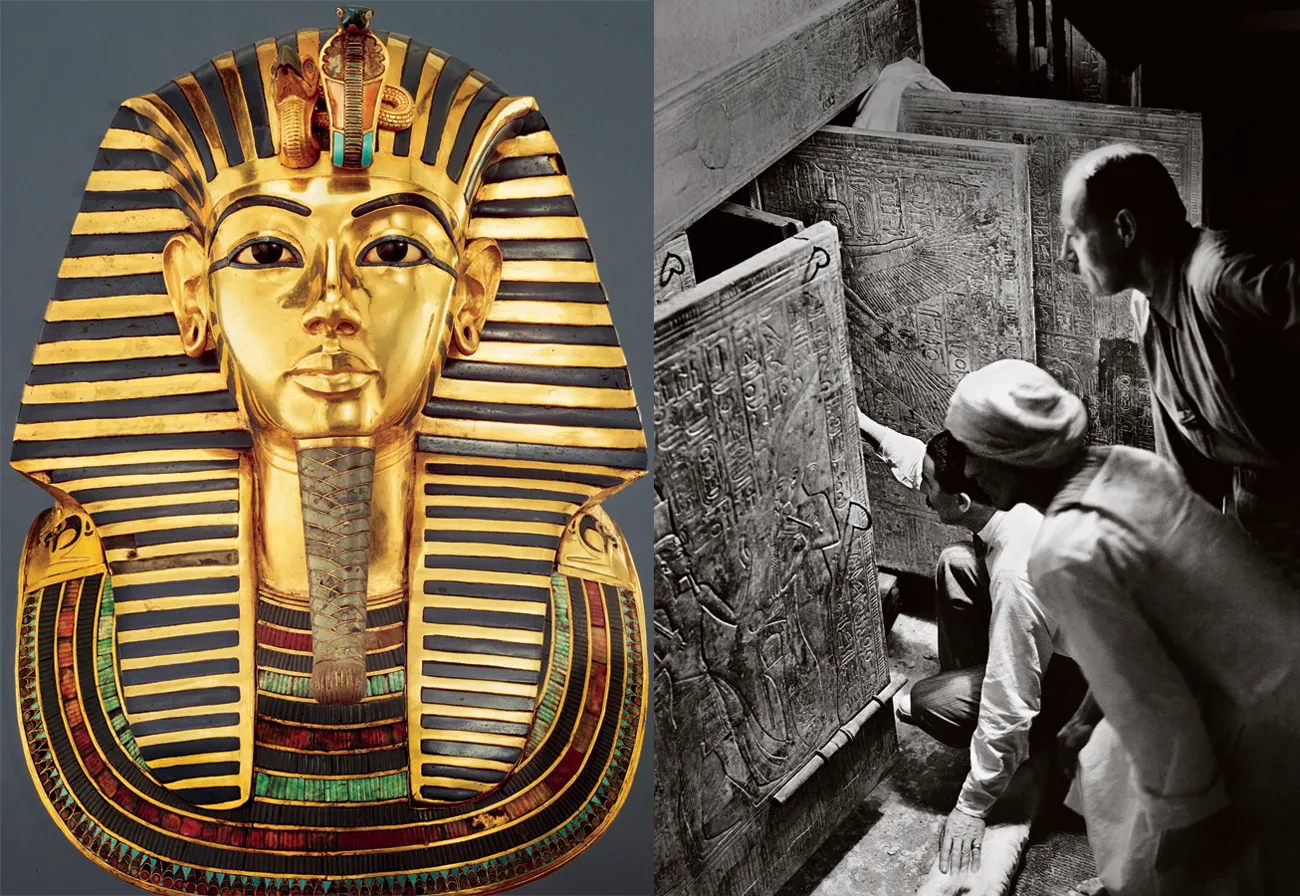

What Carter uncovered is now regarded as one of the greatest finds in the history of archaeology: a complete set of royal coffins from the pharaonic New Kingdom era, lavishly wrought and in a startling state of preservation, with, at their centre, the mummified remains of a teenage king beneath a gold and blue “death mask”, that would eventually be seen by millions in exhibitions around the world and which would come to represent the magnificence of Ancient Egypt.

It was on November 1, 1922, that Carter began clearing a row of ancient stone huts, formerly used by workmen and close to a much larger tomb, rubble from which was strewn around the site. Three days into the task, on November 4, a single stone step emerged-the top of a flight that had been dug down into the limestone bedrock some 3,000 years earlier to carve out a smaller-than-average burial chamber and surrounding storage rooms.

By sunset the following day, a blocked doorway at the bottom of the stairs had been reached. It was plastered over and, crucially, bore the seal of the royal necropolis. Carter sent a telegram to Lord Carnarvon telling him of his wonderful discovery in Valley a magnificent tomb with seals intact”.

It was another three weeks before a group consisting of Carter, Carnarvon, engineer Arthur Callender and Carnarvon’s daughter. Lady Evelyn Herbert, stood at a second doorway at the end of a corridor, cleared of debris, while Carter chiselled a hole to peer by candlelight, into the royal antechamber, filled with gold and ebony artefacts.

For the next three months, Carter and his team- including photographer Harry Burton from the Metropolitan Museum in New York and the Met’s Egyptologist, Arthur Mace- continued their excavation until, in February 1923, they had reached the burial chamber itself, containing four gilded wooden shrines enclosing the sarcophagus that housed Tutankhamun’s mummified body. It would be another two years, the start of the season in October 1925, before Carter would come face to face with the now-iconic gold funerary mask, found in a solid gold coffin enclosed by two larger coffins within the sarcophagus. Carter’s cataloguing of all king Tutankhamun’s treasures would continue until 1932.

“Tutmania” spread across the globe as news of Carter’s achievement was reported. Amid the political fallout from the discovery – Egypt had been a British protectorate during World War I, but declared its independence in 1922 visitor numbers soared and the cult of “King Tut” was born. The death from a mosquito bite, of Lord Carnarvon in April 1923, fed into the popular belief in the “Mummy’s curse” – the inevitable downfall of those who disturb the pharoah’s resting place.

This autumn, Egypt will hope, once again, to attract world attention as its long-awaited replacement for its antiquities museum in Cairo’s Tahrir Square – home to the Tutankhamun treasures for many decades- opens only a mile from the Pyramids at Giza. The monumental Grand Egyptian Museum, 20 years in the construction and costing over a billion dollars, will bring together for the first time all 5,000 pieces painstakingly retrieved by Carter a century ago.

Picture Credit : Google