You must have often read about genetically modified organism (GMO) in newspapers. Let us know about it.

What is GMO?

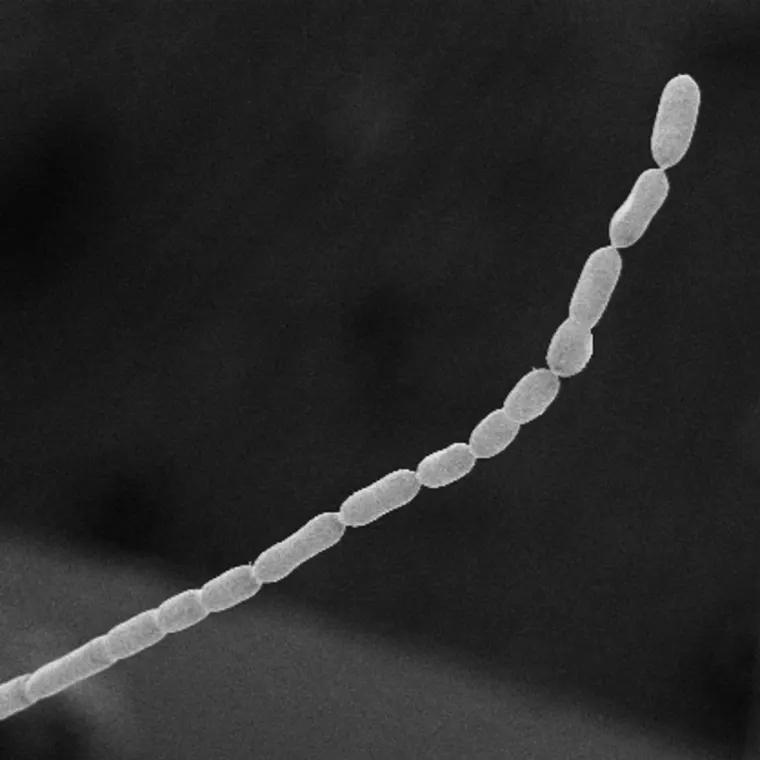

GMO is an animal, plant, or microbe whose DNA has been altered using genetic engineering techniques. Genetically modified animals are mainly used for research purposes, while genetically modified plants are common in today’s food supply.

The specific targeted modification of DNA using biotechnology has allowed scientists to improve the genetic makeup of an organism without unwanted characteristics.

History

For thousands of years, people have been using breeding methods to modify organisms. Corn, cattle, and even dogs have been selectively bred to have certain desired traits.

The conventional methods- selective breeding and crossbreeding-can take a long time. Meanwhile, these methods often produce mixed results, with unwanted traits appearing alongside desired characteristics.

In last few decades, modern advances in biotechnology have allowed scientists to directly modify the DNA of microorganisms, crops, and animals. Genetically modified foods were first approved for human consumption in the U.S. in 1994.

Present day

GMOS produced through genetic technology have become a part of everyday life, entering society through agriculture, medicine, research, and environmental management.

Today, approximately 90% of the corn, soybeans, and sugar beets in the market are GMOS.

Pros and cons

While GMOs have been a benefit to human society in many ways, the production of GMOs remains a highly controversial topic in many parts of the world.

Genetically engineered crop produce higher yields, have a longer shelf life, are resistant to diseases and pests, and even taste better. These benefits are plus for both farmers and consumers.

However, genetic engineering raises the possible risk of unexpected allergic reactions to some GMO foods.

Also, genetic engineering changes an organism in a way that would not occur naturally scientists insert genes into an organism from an entirely different organism.

Picture Credit : Google