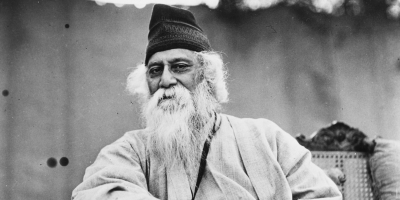

The board of Bengal, Rabindranath Tagore was the first Indian to receive a Nobel Prize, one of the highest honours in the world. He won the prize in the Literature category in 1913 for his poetry collection “Gitanjali”.

Born in 1891 in Calcutta (now Kolkata), Tagore was well known for his poetry, songs, stories, dramas, which included portrayals of people’s lives, philosophy and social issues.

Born in a wealthy family, Tagore was home-schooled, but went to England to study further. A few years later, he returned to India without a formal degree. While managing his family’s estates, he got a closer look at the impoverished rural Bengal. A friend of Mahatma Gandhi, Tagore participated in India’s struggle for independence. In fact, the national anthem that we sing today is one of the many stanzas of hymn composed by Tagore.

While he originally wrote in Bengali, Tagore reached out to a wider audience by translating his works into English. “Gitanjali” is a collection of more than 150 poems, which includes Tagore’s own translations of some of his Bengali poems. It was originally published in Bengali in 1910 and in English in 1912, with a preface by English poet W.B. Yeats. Some of Tagore’s acclaimed works include “Ghare Baire” (“The Home and the World”); “Sesher Kabita” (“Farewell My Friends”). “Kabuliwala”, “Gora”, “My Boyhood Days”, “Gitabitan, “and “The Post Office”.

Following the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre in 1919, Tagore returned his Knighthood for Services to Literature, which g=he was awarded in 1915.

Through his ideas of peace and spiritual harmony, the Nobel Laureate paved a new way of life based on his ideals of Brahmo Samaj. His contribution to education too is unparalleled. He founded the Visva Bharti University in Santiniketan, focusing on developing the child’s imagination and promoting stress-free learning.

Tagore passed away in 1941 at the age of 80.

Picture Credit : Google